- As a business with active commodity trading and lending strategies in agriculture and energy we are constantly monitoring Chinese liquidity measures as this function is highly correlated with prices.

- China stands out as the sole major economy trying to slow money supply in fear of repeating the over stimulation of the 2009-2011 period.

- In contrast the Western World Governments seemed to be buoyed by the outcomes of monetary policy since the 2008 crisis and are showing a deep commitment to “as much monetary and fiscal policy as it takes” to over inflate their economies.

- Until recent weeks, commodity prices had not yet reacted to the Chinese tightening, however the last few weeks have seen the first crack in pricing.

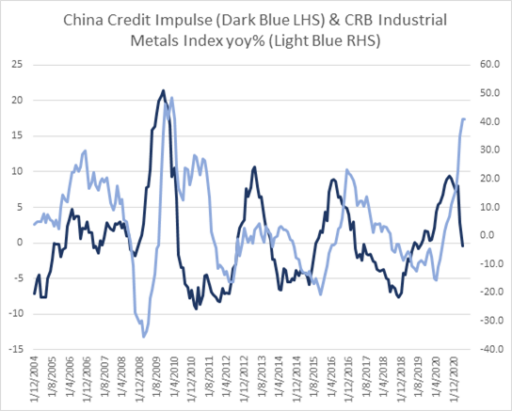

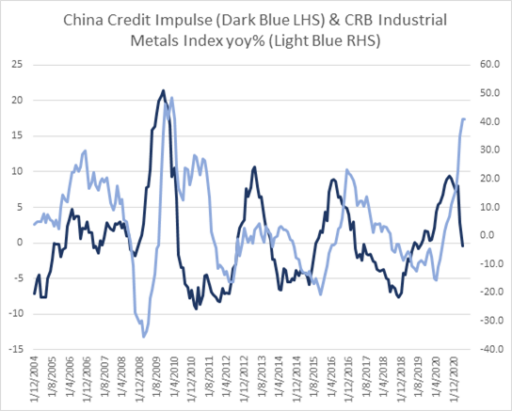

The China Credit Impulse is an important indicator for investors as it generally leads the global economy. It measures the change in the growth rate of aggregate credit as a percentage of gross domestic product and includes all lending, not just bank credit. The growth in the flow of credit throughout the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic last year was one of the key factors – along with unprecedented global fiscal and monetary policy stimulus – to support the global recovery.

The China Credit Impulse peaked in October last year and, more recently, has moved into negative territory. The slowdown in growth has been more rapid than in previous cycles – from peak to negative has taken 7 months compared with 9-10 months in the past – and a more recent plunge has come after the Chinese central bank asked major lenders to “curtail loan growth for the rest of this year after a surge in the first two months stoked bubble risks.”

The Credit Impulse initially hits assets that are driven primarily by the Chinese economy (including industrial metals, shown below), followed by inflation breakevens and sovereign yields in Western economies. The peak correlation with other growth-sensitive assets has a bigger lag (around 12 months) but eventually most asset markets are affected to some degree.

In addition to cooling credit growth, Chinese authorities have been acting to limit speculation in commodity prices. This week the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) announced it will strengthen price controls on a range of major commodities to address price volatility. Other measures aimed at controlling prices and volatility have included the (reported) banning of commodity-linked product sales to retail investors, increasing the margin requirements and/or transaction fees for some futures trading, discouraging exports of steel products via export and import tariff changes, and calls for large Chinese companies to increase supply and control prices.

Prices drive prices, and Chinese authorities are attempting to short-circuit the positive feedback loop of “commodities as an inflation hedge”. The range of measures has contributed to significant falls in the prices for various commodities including iron ore, copper, palm oil, corn, wheat, soybean, soybean oil and canola – many of which had recently reached multi-year or all-time record highs.

The combination of Chinese price controls and the drop in credit growth will act as a headwind to inflation, but an important factor in this cycle will be stimulatory fiscal and monetary policies in the rest of the world, as well as the shifting approach from central banks such as the US Federal Reserve to tolerate higher levels of inflation.

In terms of investment decisions, the strong pull-back in credit from China is negative for “risk” assets but the overall impact on inflation will be less certain. The current debate about whether the rise in inflation is transitory, and that current easy monetary policy will eventually require a heavy-handed response, is unlikely to be resolved any time soon.